“They Were Just Themselves There”:

Chris O’Dell On Let It Be, Get Back & The Beatles Last Days At Apple

On the Apple roof, O’Dell is seated on the far right on the bench behind George Harrison

Apple Corps Ltd

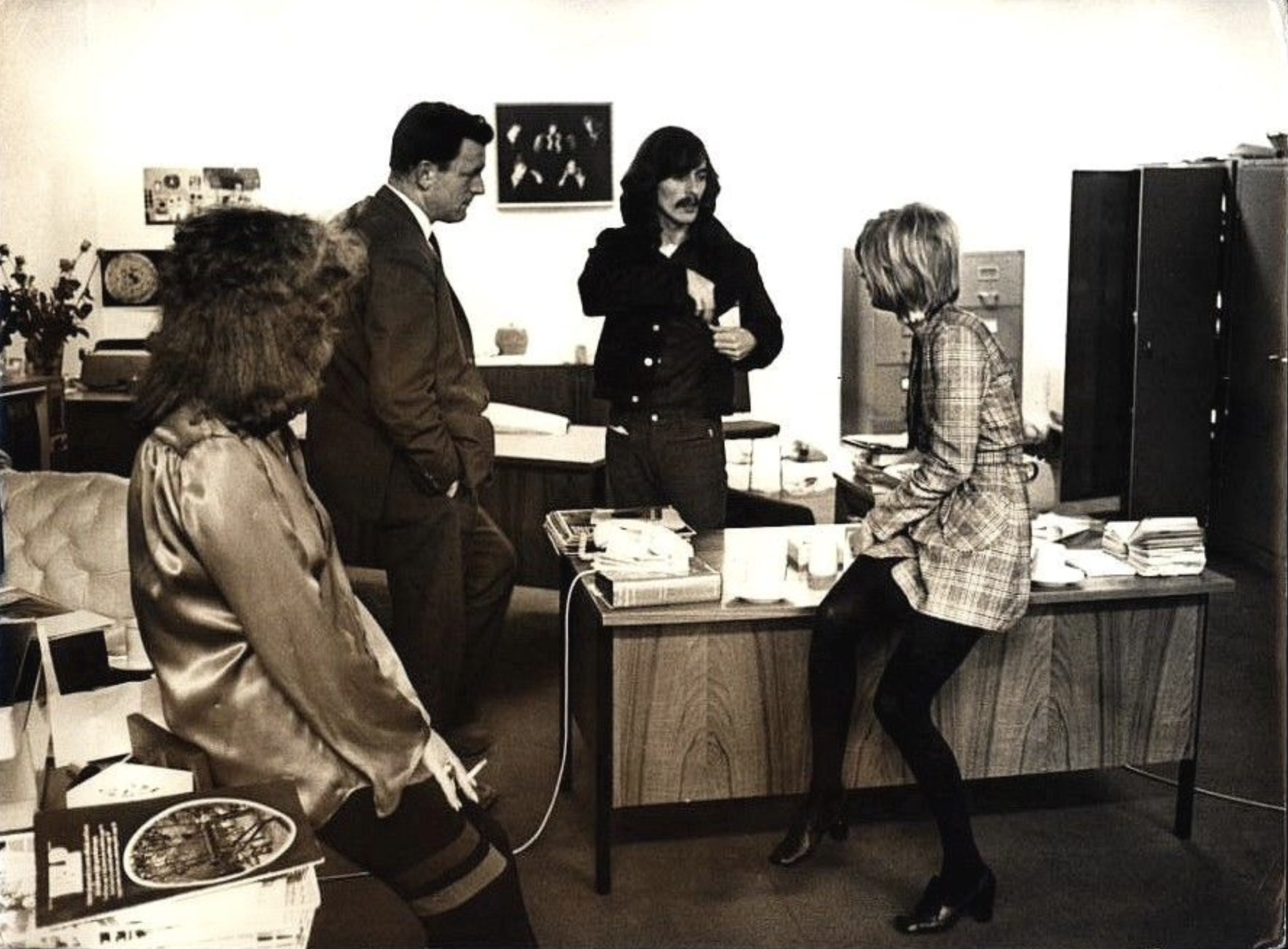

Chris O’Dell with George Harrison & Derek Taylor at the Apple offices

From a distance, the sixties seem like a dream. Extraordinary change swept over the world in ways that were both gradual and sudden, dovetailing into an explosion of creativity and expression that impacted everyone and everything. The fashions, music and mindset has been romanticized and sought after ever since - a new world remade by a youth culture that had collectively unburdened itself of inhibition, whose art was reflective of a new way of living and being. But all things must pass. Proof of it all would stick around, though the sunshine would fade, withering like the flowers that came to symbolize the decade and its sea change. Some kind of utopia wasn’t that simple or sustainable, and by 1970, neither were The Beatles. Harmony had always been a part of their story and appeal, their very friendships synonymous with the hippie ideals and All You Need Is Love ethos they turned into song. Although the Let It Be movie had lifted the curtain during a time of difficulty. They had set out to film themselves recording a new album, but instead provided a birds eye view of their collapse. With the November 2021 release of Peter Jackson’s three part Get Back, that long held image of total discord has been somewhat revised. For the first time, viewers are given a glimpse of the 55 + hours of footage that was never used. In its place is a fuller picture of events that’s decidedly lighter, more human and emotionally complex than anyone who wasn’t there has ever known it to be.

Immortalized in the 1973 George Harrison song, “Miss O’Dell,” Chris O’Dell was a trailblazer in the music scene, becoming one of the first - if not the first - women tour managers in rock and roll. But back in 1968, the Tucson native was working in LA in an uninspiring clerical position. Then, on a night like any other, she unexpectedly met Beatles press officer Derek Taylor at a party. They struck up a friendship and what could have been the end of the adventure turned out to only be the beginning. Taylor spoke about Apple, the first of its kind venture the band was about to launch, and repeatedly told O’Dell she should consider coming to London. She eventually sold her record collection for two hundred dollars and flew across the Atlantic, unsure if there was indeed a job for her there, but willing to risk it all to find out.

Derek Taylor

“When you’re twenty years old, things are different,” she laughs. “Would I do that today? Well of course not. But would I have done that in my forties? I don’t know. But twenty? It was like, ‘Oh anythings possible.’ So I jumped headfirst into it and kind of took it as it came. I think that I was pretty fascinated by everything because I was in England, I’d never been there before, and with four of the most famous people in the world.”

Launched by The Beatles in 1968, Apple Corps Ltd began as a multimedia company encompassing records, retail, publishing, film and electronics. It was an opportunity for the group to take control of their finances and future, while simultaneously establishing a forward thinking enterprise that valued creative innovation. Incredibly, the entire operation consisted of a small team that, when O’Dell first arrived, amounted to one floor of a building on London’s Wigmore Street. They later moved their headquarters into Savile Row.

“I don’t know how many of us were working there, but it wasn’t huge,” she says. “I mean, the building wasn’t huge.”

3 Savile Row

3 Savile Row was five stories - six when you include the basement that would eventually be turned into a studio. When she estimates that there may have been only four or five people on a floor, with probably the greatest number of employees in the press office, I marvel at the modest size of the staff working for the biggest band on the planet.

“Yeah,” she agrees. “It wasn’t a corporation.”

Photographs and footage of the longhaired band members and their fans outside the towering Georgian structure is a familiar one, though it’s easy to forget that their very existence there was the ultimate definition of two worlds colliding.

“Of course it was a very snobby street,” she remembers with a laugh. “It was tailors row and that was the Queen’s tailor. They were all there and they were the guys in the top hats. So it was an odd choice in a way, but it was also so beautifully located.”

Savile Row in the mid 60s

The Beatles on the Apple rooftop

For the band, Apple was largely a hands on endeavor, which meant that they, especially Paul, could be there at any time. And because they might be there, everybody else wanted to be there, too.

“Everybody came around when they were in London,” she says, describing how whispers of arrivals from the likes of Lauren Bacall and Duane Eddy often “traveled down the grapevine.”

“It was like that a lot and the word would travel through, we would kind of know who was there. It would get to us somehow.”

She initially did odd jobs around the office before working directly for A & R manager, Peter Asher, and later George Harrison. I ask what she thought of The Beatles when they first met, and if their individual personalities aligned with her previous perception.

Paul McCartney

“I think Paul seemed a little bit more mature than I had seen him in my mind,” she says. “He was a little bit more mature, he was very involved in the business, but very personable. I think overall, yeah, they were pretty much like I had seen them or I thought they would be. But who knows?” she admits, alluding to all the years since. “What I do know is that it was very casual and they were very casual. They were safe in that environment, so they were just themselves there.”

Chris O’Dell with George Harrison

George Harrison, Chris O’Dell and her mother

It was in those comfortable surroundings, away from the flashbulbs, that she got to know them. “I think about that now and it does kind of surprise me,” she says about the real, lasting friendships formed. “I didn’t think so much about that then. It just felt pretty natural as I saw them a lot. But when I think back now, I think, ‘Wow, actually, I kind of forgot that they were...’ I mean, you can never forget someone’s famous because its just there, if you think you’re doing it, you’re crazy because its constantly you’re reminded of it. But in their own home and in their own space, they’re just friends. They’re just like anybody else. When you walk out the front door or go into a restaurant, then everything changes.”

Pattie Boyd, Chris O’Dell, Harold Harrison and Eileen Basich at the Concert for Bangladesh

Chris O’Dell, George Harrison’s father, Harold, & Pattie Boyd

George Harrison & Chris O’Dell

Jenny Boyd, Pattie Boyd & Chris O’Dell

Ringo Starr & Chris O’Dell

In her 2009 memoir, Miss O’Dell: My Long Days & Hard Nights With The Beatles, The Stones, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton & The Women They Loved, she wrote about singing in the chorus of voices in the second half of “Hey Jude,” witnessing their final live performance on Apple’s rooftop and being at George’s house when newspapers bearing the surprise announcement “Paul Quits The Beatles” had left fans - and the rest of the band - stunned. All of which made Get Back akin to opening up a time capsule, not just for its fly on the wall vantage point, but because of the cutting edge technology that restored color and clarity to the original footage. “Actually the interesting thing about it is that it took me back,” she says when discussing how surreal it felt to watch. “It’s like seeing something that happened in your life 51 years later, but actually it looks like it’s just happening, like it was taken yesterday.”

Chris O’Dell, Linda & Heather Eastman in Get Back

Yoko Ono, Maureen Starkey, Ken Mainsfeld & Chris O’Dell in Get Back

But the superior image quality is not the only vibrant thing about the film. The heavy weight of Let It Be ebbs and flows before all but disappearing. Like its predecessor, Get Back captures uncomfortable moments of disagreement, but it also shows much more of what followed. By the time we see the Beatles leave Twickenham studios for Apple’s basement, now joined by old friend and accompanying musician, Billy Preston, they seem to be in a different state of mind.

“Twickenham was not a happy time, and as I recall, that is true,” she says. “Thats the way it was back then - that things were not so good at Twickenham and that when they came to Apple, things did get better for many reasons. Number one, it was a much more workable environment and they had Apple support there to help with things if they needed things done, and they had a chef there who could cook lunch so they didn’t have to go out. So it was a more comfortable environment. You know, I honestly think somewhere in there, the truth lies in the middle of the two.”

When they first entered the public’s consciousness in the early 1960s, they were almost immediately known for and defined by their individual magnetism. They were so funny and natural, they exuded charisma wherever they went. Throughout Get Back, they are often very obviously playing to the camera, aiming their silly faces or jokes directly at the lens. At other points, they seem to forget they’re even there.

“On Get Back, it was probably a slight exaggeration of each other,” she says, describing what she saw of their dynamic behind closed doors versus what we see onscreen. “They were slightly exaggerated.”

I remember how many times I’ve seen or felt the presence of a camera change the air in a room, and I wonder if it was because they knew they were being filmed.

“Absolutely,” she replies. “Actually I was amazed at how many times they let their guards down knowing the cameras were on.”

For John, their ubiquity seemed to be energizing.

“John was particularly bouncy in Get Back for a extended period of time, I don’t think he was like that all the time. He was like that, but not as much as you saw in there,” she says, before later discussing how she felt that Ringo’s one of a kind nature and character is so much bigger.

“They just had him sitting there all the time just being so patient, and he was very patient, but his personality is really amazing and I just think in some ways it missed that.”

Watching the band run through sketches of “Let It Be,” “Something,” “Octopus’s Garden” and “Two of Us,” it’s clear that, even in turmoil, they couldn’t help but fit together perfectly. It was a closeness that began when John, Paul and George were teenagers in Liverpool, and was later solidified during long residencies performing in Hamburg, Germany. Ringo, then drumming for fellow Liverpool outfit Rory Storm & The Hurricanes, was also touring there when he became their friend, although he didn’t officially join until 1962.

George Harrison, Paul McCartney and John Lennon

Ringo Starr and George Harrison

“From the time they got together through Hamburg, to the time they came back and things started to pick up for them, they had spent a lot of time together,” she says. “A lot. In Hamburg, they were in the same room, basically, all the time you know, sleeping and everything. So they knew each other really well. The Liverpool sense of humor is extremely funny and it’s what we see when they do that in front of the cameras: that wit, that quick comeback. And they were like that, for sure. That was part of where they came from, of their culture, I believe.”

Besides childhood bonds, the entire Beatlemania experience was a form of being in the trenches together, a fact that made any animosity sure to eventually run its course. For a time, Paul and George’s relationship was a particular source of speculation after a heated exchange - shown in both Let It Be and Get Back - comes some time before George eventually walks out of sessions, temporarily quitting the band.

“I think that they had probably a difficult relationship but the most important thing to remember with them, and I heard it from them: ‘Only the other three people know what it’s been like, it’s only four of us who shared that experience,’” she remembers, describing the profound connection they all felt. “And that’s so bonding that no matter whether they agree, don’t agree or don’t speak for years or whatever, they still will come back to each other because they went through all of that together.”

Even still, we watch Get Back knowing that they would make just one more album: Abbey Road.

Outtakes from the Abbey Road cover photoshoot

“Did we know there were problems? Absolutely,” she says. “But did we see it as unfixable? I don’t think so. I think everybody thought, ‘Oh, yeah, ok, they’ll get through this.’”

Yet nothing ever seemed to ever stop them from writing. More than a few compositions they are shown rehearsing during the Let It Be sessions end up on Abbey Road, while a few more will later appear on some of their early solo offerings. And while it’s hard to know exactly what their intentions were, everything about the last songs they would record as The Beatles does feel like a goodbye.

“Abbey Road in a way was the finale,” she concludes. “I remember when it came upstairs, the demo came up to the press office and they played it. It was like, ‘Wow, this is seriously good.’ But it certainly has an ending.”

At the time of their breakup, O’Dell was working for Harrison and living with him and his then wife, Pattie Boyd, at their newly purchased Friar Park home. As George began recording his first independent release, 1970’s All Things Must Pass, she scheduled studio sessions and typed up song lyrics. The beloved album, recently reissued to mark its fiftieth anniversary, remains perhaps the most definitive window into Harrison’s unique perspective as a songwriter. It was an unusual, strikingly original vantage point that even his earliest efforts with The Beatles held close. “I think he was always looking deeper at things than probably a lot of people were at that age,” she says. “That was who he was.”

George Harrison

In 1974, she found herself living in the same Malibu beach house as John Lennon, May Pang, Harry Nilsson, Ringo Starr, Keith Moon, and Klaus Voorman. “It was like summer camp,” she says. “You didn’t know what anybody was going to do.” Lennon was producing Nilsson’s record, Pussycats, and the residence had been rented as a place for all of the musicians to stay. People were always stopping by, though the most notable guest was Paul McCartney. He and Lennon had not seen one another since the bands very public rupture had left them on bad terms, and sadly, Pang’s photos of them together would be the last ever taken. Historically, it’s remembered as the moment the ice began to thaw.

“It was a pretty important moment because they hadn’t seen each other for quite a while, since the breakup and everything,” she says, before describing how it felt right to give them space. “Many of us just disappeared. There were other people living there, too and we just kind of disappeared and left them to their own thing. It was friendly, it was natural, but it was the first time. So it was good to just sort of let them all sit and do their thing alone.”

Long after her whirlwind days at Apple, O’Dell continued in the industry, working with the Eric Clapton led Derek and The Dominos, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Grateful Dead, Frank Zappa, Fleetwood Mac, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, Electric Light Orchestra, Linda Ronstadt, Queen, Phil Collins, Bob Dylan and more.

Chris O’Dell and friends at Harry Nilsson’s wedding

Newspaper clipping: Chris O’Dell, Bianca Jagger, Mick Jagger and Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegan

Chris O’Dell (far left) pictured in the crowd with George Harrison and Pattie Boyd at the 1969 Isle of Wight

Chris O’Dell, Billy Preston, Ravi Shankar, George Harrison and friends on Halloween

Harry Nilsson, Chris O’Dell and George Harrison

Chris O’Dell and Mick Jagger

Chris O’Dell backstage with Bob Dylan

Chris O’Dell and Mick Jagger

Chris O’Dell at Apple with George Harrison

In the early 1980s, she decided to leave the business and go back to school, receiving both her college degree and masters degree in counseling psychology. She embarked on a second career as a therapist, though she briefly returned to the road for a 2004 tour with Linda Ronstadt.

Now retired and back in Tucson, Arizona, her ties to music’s most studied and celebrated generation remain preserved both in her memory and the art itself.

In addition to the George penned “Miss O’Dell,” she inspired Leon Russell’s “Pisces Apple Lady” and “Hummingbird.” She is the “woman down the hall,” in the Joni Mitchell song, “Coyote,” and her picture can be seen on the back cover of The Stones 1972 masterpiece, Exile on Main Street. Although as she tells me in March of 2022, working for The Beatles was the most exciting, and I’m not surprised. In the sixties and beyond, they are woven into the fabric of the culture they helped shaped so completely, its impossible to imagine the world without them. They are a part of everyone’s story.

But how many people got to be a part of theirs?

by Caitlin Phillips

5.31.22